Russ Ackoff shared that the best knowledge system he knew was to have an intelligent set of graduate students that knew him. In 1985 when we were meeting regularly, he described the joy every morning of coming in and having 2-3 journal articles taped to his office door that his students thought were relevant for him in the moment. He pointed out that the students knew his interests and his current projects and would look out for material they knew Russ would be interested in. Russ chuckled and shared “graduate students are much better than any search engine could ever be.”

To Russ’s observations I would add that colleagues and professors who know me are also a great source of knowledge pointers, if I just remember to include them in what I am up to.

I mentioned to my colleagues at UW Bothell that are working on the future designs for innovative universities that I was headed back to Durham, NC, where I hoped to meet with Cathy Davidson. Gray Kochhar-Lindgren suggested that I also try and meet with Kate Hayles while I was at Duke. Both professors were available and I looked forward to the meetings.

As I prepared for the meetings, I remembered another conversation with Russ Ackoff where he talked about his favorite design for a graduate seminar with his second and third year PhD students. The class had only one assignment – each student had to teach Russ something that he didn’t already know. With his impish grin, Russ described how much fun the first couple of weeks of the seminar were as the students went from thinking this class was a breeze to it dawning on them how hard it was going to be to figure out what Russ already knew. He enjoyed the different strategies the students employed to “discover” what he already knew.

Russ delighted in the new things that he learned each semester. However, he particularly loved how much he was able to impart to the students without ever having to lecture. The students had to learn a large portion of what he already knew (which in my limited life experience was huge as Russ was the best systems thinker and synthesist I’ve ever encountered).

If you asked me two months ago if I was interested in learning anything new about the digital humanities, the answer was an emphatic “No.” Yet after spending time with Alan Wood, a Chinese History professor, Susan Jeffords, an English professor (now UW Bothell Vice Chancellor), Gray Kochhar-Lindgren, a philosophy professor, and Jan Spyridakis, a technical communications professor (now Human Centered Design and Engineering Department Chair), my exposure to the humanities had increased by light years compared to the previous forty years of professional life. The “Ah Hah!” moment that I needed to spend some serious time understanding the digital humanities came at the recent Modern Language Association meeting in Seattle where two English professors talked about Big Data and two computer scientists talked about the need for digital storytelling to go with their worlds of Big Data. The world it is a shiftin’.

I was familiar with Cathy Davidson’s work through my research over the last two months, but I was unfamiliar with Kate Hayles work. So I went to Amazon to see if Kate had written any books and out popped a list of several interesting titles. I didn’t recognize any of them, but before I ordered them, I checked my Kindle library (nothing) and I went to Librarything to see if I had any of her books. Sure enough, I’d ordered and read Writing Machines. One of these days I’m going to have to do a better job of remembering author’s names. So I ordered several of Kate’s books (How We Became Posthuman, My Mother was a Computer, and Electronic Literature). Two of the books were on the Kindle so I could scan through them pretty quickly for the key themes.

As I made my way to the Smith Warehouse where Cathy has her office, I marveled at how much the Duke campus had changed over time. When I went to Duke (1967-1971), the Smith Warehouse was literally a tobacco warehouse. Any time you came near the building you were assaulted with the cloying smell of tobacco leaves being aged and dried. Now it was a beautifully remodeled space of bricks and 100 year old wooden beams and floors. I was reminded of Stewart Brand’s How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They’re Built.

As I made my way to the Smith Warehouse where Cathy has her office, I marveled at how much the Duke campus had changed over time. When I went to Duke (1967-1971), the Smith Warehouse was literally a tobacco warehouse. Any time you came near the building you were assaulted with the cloying smell of tobacco leaves being aged and dried. Now it was a beautifully remodeled space of bricks and 100 year old wooden beams and floors. I was reminded of Stewart Brand’s How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They’re Built.

The primary topic I wanted to explore with both professors was what qualities they thought were important for an idealized design of an innovative university. Each professor was quite articulate about their ideas for the key qualities of the new university or the new humanities department. The short version of these qualities is:

- Collaboration and Collaboration by Difference

- Provide flexible spaces for collaboration that can be easily re-configured

- Rethink the curriculum to be multi-disciplinary and jettison many of the ossified department structures

- Shorten the formal school year to end in March with the rest of the second semester spent in community based projects where professors, graduate students and undergraduate students from multiple disciplines team up with community members to work on important local problems.

Cathy emphasized many of the issues she raises in her books and her consulting with corporations. She shared “we have to move from an educational model which is based on testing and mastering content to a learning model that is focused on process, collaboration and learning to learn.” She quoted from sources that describe that the average college graduate will change careers 4-6 times during their lifetime. Not just change jobs, but change careers. She described how every time she talks to corporate groups, the business executives demand that we change the way we teach. Most of these business people say some variant of “it takes us two years with recent college graduates to break them of their pursuit of individual mastery and being scared of being wrong to getting them comfortable with not knowing so that they can collaborate with a diverse group of professionals with different skills.” Their plea is to stop turning out students with skills that business doesn’t need.

The more I talked with Cathy, the more I wondered how I had missed this transition in the humanities departments from being book based to being digitally based. I finally asked Cathy how long has this transition been going on. She reflected that it was about five years ago when humanities professors started paying serious attention to how computing could help their research and pedagogy.

I shared with Cathy that I was going to a Duke basketball game that evening with my nephew. Cathy immediately used that topic to springboard to what she had learned from the social environment of Duke basketball games and how she changed her class structure. “Did you know that each year there is a student governance committee for Krzyzewskiville that takes the rules that the university mandates and then turns it into that years constitution for K-ville? Can you believe that this system has worked since 1986? Think about all of the issues of students camping out and the nature of 17-21 year olds potentially getting into fights and having drugs and alcohol. There is no way it should have worked even for one year, let alone since 1986. If you look at the ‘constitutions’ that are generated each year, they are far more comprehensive and restrictive than what Duke University requires. So I decided to do that with my class.”

I loved the turn this conversation was taking. I asked “I’ve tried to read everything you’ve written including your more recent voluminous Tweets and blog entries and I don’t remember seeing a discussion about starting your class with a constitution development. How long does it take?”

Cathy realized that she had not written more than a paragraph about this process and made a note to herself to write a blog entry about it. Upon reflection, she shared “it usually takes between one and two class periods with a lot of homework crafting the Google Doc that has the constitution. These are class periods where we’d be discussing the syllabus anyhow, but now it becomes the students’ syllabus. The students always require more work than I would require. And in the process about 20% of the registered students drop out, but that is OK as there is always a long waiting list.”

I can’t wait to see the blog entry and see some examples of both the K-ville constitutions and the course constitutions. I will be interested to see how these constitutions relate to what Jim and Michelle McCarthy are trying to do with their Core Protocols for producing great teams who produce great products.

As I walked out of the Smith Warehouse and started my walk to Duke’s East Campus to meet with Kate Hayles my head was hurting with the implications of Cathy’s research and observations for the future of business as well as the future of the university. I was shaking my head wondering how I’d missed this transition in the humanities to a digitally based paradigm.

Then I remembered that I’d glimpsed this world when I came across Franco Moretti’s Graphs, Maps, Trees: Abstract Models for Literary History (and the recent response to it – Reading Graphs, Maps, Trees – critical responses to Franco Moretti). I bought the book more for its collection of visualizations in a topic area I wasn’t familiar with. I was fascinated with the notion of “distant reading” that the author espoused. Yet, like a lot of other concepts I’ve encountered over the years, I did not do much with it.

With my trusty iPhone 4S smart phone I was able to navigate my way to Kate’s office. What did we ever do to make our way in the world without these amazing devices?

I was less prepared for my meeting with Kate Hayles than I like to be. However, she was very gracious and engaging and asked for some of the background on why I wanted to meet with her. I described a little bit of my background and that Gray Kochhar-Lindgren had suggested that I meet with her so that we could gain her insights on how to design the idealized university.

As we talked she made notes of some of her books that might be of interest to my intellectual pursuits. We started with a discussion of what her proposal for the restructuring of digital humanities looked like:

- Restructure humanities as a comparative study rather than being organized by either nationality (American, British, French), genre, or by century. She suggests that epochs now be defined by their medium (oral, print, digital) as the lines between previous ways of characterizing humanities are quite blurred.

- Shift how we think. Digital humanities is shifting not just the answers but also the questions. Digital humanities is a “technogenesis” as we are co-evolving along with the media. Technology has changed how we read and we are changing neurologically as we read and use technology differently.

- Understand that electronic literature is different than print literature. Computation is now a theoretical issue for the humanities, not just for the sciences.

The core part of the transformation to digital humanities is understanding that the overwhelming focus on print as the medium for the last 300 years has evolved to a new digital medium.

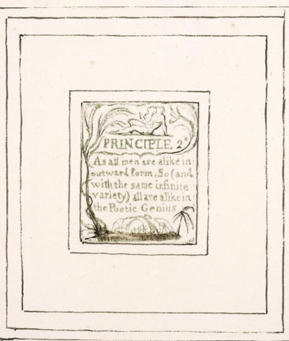

Since I am mostly a bottom up kind of thinker, I asked Kate to give me an example of what she meant. She pointed to an example in the print world of a shift in media. When William Blake first published his poems he wanted complete control of the publishing process as he wanted his poetry “read” surrounded by appropriate artwork (see William Blake Archive).

The reader of the original poetry would have a very different experience than a more modern print edition of The Poems of William Blake which is just the plain text:

Similarly, Kate pointed out that when print “texts” are translated into the digital medium they become different. They are “read” differently.

A recent Wall Street Journal article describes this shift in media as “Blowing Up the Book”. One of the adaptations to eBook format mentioned in the article is T.S. Eliot’s “The Wasteland.” This iPad app “includes a facsimile of the manuscript with edits by Ezra Pound, readings by Eliot recorded in 1933 and 1947 and a video performance of the poem by actress Fiona Shaw.”

If you compare the print version of the poem with the enhanced version there is a very different understanding of the poem in the electronic version than in just the “plain text.” The following three screen shots give you a sense of the richness of the electronic version:

My favorite “digital media” variant within the app is Fiona Shaw performing the poem while the poem’s text is also presented on screen with the current line of the poem she is speaking highlighted in blue.

Slowly but surely I was beginning to get a sense of what Kate was describing. This discussion started reminding me of the philosophical question “Can you step into the same river twice?”

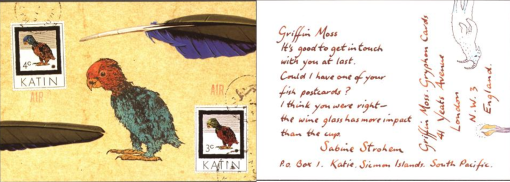

As I look at these new forms of digital text where the text is embedded in art, I reflected on a recent conversation with Jim and Michelle McCarthy where they showed me examples of reports they gave to clients. These reports were fragments of text placed on top of the team art that was generated during one of their Bootcamp weeks. Both of these discussions reminded me of Nick Bantock’s series of books that started with Griffin & Sabine: An Extraordinary Corespondence. Bantock created a book as a series of illustrated postcards and letters for the user to “experience” the correspondence.

Given the power of the inclusion of team art on the Bootcamp weekend, I wondered if we should be doing that with our emails. Instead of sending plain text emails, we should surround our text with appropriate art to reinforce our message. Stan Davis in The Art of Business suggests that the absence of art in the workplace was one of the explanations for the lack of creativity and innovation.

Then, Kate hit me with the real paradigm shift here. Along with comparing “texts” across different media, she is using literary critique skills to critique code. She described this emerging field of critical code studies. I wasn’t sure I had really heard what she just said so I asked for a specific example.

Kate explained “We are now as interested in critiquing the software as we are in critiquing the text. There are several efforts under way to have side by side displays of the ‘digital text’ and the software that implements the digital text.” Now I knew that I had just fallen down Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland rabbit hole.

Kate explained “We are now as interested in critiquing the software as we are in critiquing the text. There are several efforts under way to have side by side displays of the ‘digital text’ and the software that implements the digital text.” Now I knew that I had just fallen down Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland rabbit hole.

“Let me see if I understand this right,” I asked. “You mean to tell me that Humanities students are both interested in software and have the ability to critique and write software in an humanities course?”

Kate looked at me a bit like I was a Freshman student, and patiently explained “of course, this current generation is interested in software. This is the digital native generation and they are eager to do the software explorations. They are frustrated with those of us from the old school who only want to focus on print.”

“Let me try one more time. There are not any humanities majors I know (including one of my children) who have the least bit of interest in computing. They chose the humanities so they could stay away from science, math, and computation,” I asserted.

Kate just smiled and suggested that I ought to sit in on one of her classes where they do exactly what she is describing – study comparative literature by creating and critiquing software. Kate said that given this turn in the conversation she would send along a couple more chapters from her latest book.

I knew that I needed more grounding in what Kate was describing so I asked for some specific examples. She pointed me to Mark Marino’s Critical Code Studies to give me an overview of this simultaneous critique of the text and the code. Another researcher in this area is Alan Liu with his Research-oriented Social Environment (RoSE) project. She suggested I look at John Cayley. I particularly liked Cayley’s Zero-Count Stitching or generative poetry (I wonder if somebody will combine Zero-Count Stitching with the generative poetry on Sifteo Cubes).

However, the example that really grounded me in what Kate was trying to articulate was Romeo and Juliet: A Facebook Tragedy. This research project involved a group of three students translating Romeo and Juliet into Facebook. The students described their results:

“Reading the story as we have created it requires users to navigate through various Facebook features such as the “Wall,” “Groups,” “Photos,” and “Events.” Following the story in this way is similar to a work of hypertext fiction. However, the advantage offered by Facebook is that the interactions are ordered and timestamped, allowing for users to more easily discern which interactions come first in which progressions. We feel that this means of presenting a story offers a benefit of hypertext, forcing users to interact with the text, but at the same time it cuts down on much of the confusion by clearly communicating the progression of the overall plot.

“Manufacturing character profiles based on the limited information in the text was difficult. We relied on individual interpretation and key themes surrounding each character. We supplied interests, books, movies, music, etc. that individuals with those character traits and personality types would be likely to enjoy. Character development was further facilitated by use of various applications and groups which we had characters add or join in order to reflect what we interpreted as their key traits. We feel we have provided somewhat more complete profiles for each character, hopefully to the aim of making them more relatable and providing more depth.

“The project also unexpectedly became an exploration of how virtual role-playing could potentially produce a simulation or model of events in plays and/or novels. Despite the limited nature of the character profiles offered in the original text, enough detail was present to conclude certain character types and the ways that certain characters would act. With close reading, we were presented with certain constraints (ie: character traits, personalities, and relationships), and we had to make sure that these constraints were incorporated into our simulation aside from use in the creation of the profiles. For example, Tybalt in the play is an angry character. Therefore, he was permitted to only perform angry actions and have angry interactions with others on the site. With these constraints, group members attempted to play out the rest of the story while keeping in mind that certain actions or interactions needed to occur for the plot to move forward.”

I was really hooked now and could not wait until I got back to a computer to go online and explore these links and examples. What wonderfully creative ways to learn both narrative structures and programming. I know I have just found an important source of inspiration for the next generation of “content with context” software I want to build.

“One of the most important vehicles for the digital humanities is to create projects. An example of a project at Duke is The Haiti Lab (Cathy Davidson also used this example). The project focuses on a wide range of topics associated with Haiti including art, demographics, and epidemiology. The project members provide a vertical integration with undergraduates, graduate students, post doctoral researchers, and professors,” she elaborated.

Our time was almost up and I knew I could find out more about these topics from her books, her chapters that she would send, and poking around her online references. So I moved on to ask her if she were doing an idealized design of a university, what were some of the qualities that she would want embraced in the design. Kate shared her top three qualities:

- Collaboration. The focus of everything in the new university has to be collaboration. There is just too much for any one person to master. We have to prepare students for the way of the world now – collaboration.

- Flexible spaces. Space is more bitterly fought over within the university than any other resource. Yet, our facilities are designed almost exclusively for lecture based classes. We need spaces that are open and can be reconfigured quickly with no fixed seating. We need spaces where work can be left on the walls or partitions so that they can be seen and commented on by others.

- Rethinking the curriculum. We need to jettison the categories and departments that don’t make sense anymore. So many of the departments within the university are ossified and self-perpetuating. The sciences are much better about regularly revisiting the curriculum than the humanities. The curriculum has to be multi-disciplinary.

I thanked Kate as we finished up and asked her if she would invite me back in the fall to sit in on one of her courses that explored humanities students creating the software for “digital texts.” Kindly, she thought that would be a great idea.

The next morning the three chapters she had promised from her forthcoming book How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis showed up in my inbox. On my flight back to Seattle, I read these chapters along with finishing up David Weinberger’s Too Big to Know. The unintentional reading of these two documents simultaneously shed even more light on the challenge of “networked knowledge structures” which require collaboration and story telling to make meaning. Kate shared that the timeless questions from her perspective are:

- How to do?

- Why we do?

- What it means to do?

She points out that the latter two questions are what the humanities are really good at understanding. My focus is on the first two questions. I guess we will meet in the middle.

While I was very appreciative of the work that Kate and her fellow travelers were creating, it never dawned on me that from completely different directions we might be developing the same types of tools. In Chapter 2 of How We Think, Kate pointed to the Digital Humanities Manifesto 2.0 to describe the first two waves of the new field:

“Like all media revolutions, the first wave of the digital revolution looked backward as it moved forward. Just as early codices mirrored oratorical practices, print initially mirrored the practices of high medieval manuscript culture, and film mirrored the techniques of theater, the digital first wave replicated the world of scholarly communications that print gradually codified over the course of five centuries: a world where textuality was primary and visuality and sound were secondary (and subordinated to text), even as it vastly accelerated the search and retrieval of documents, enhanced access, and altered mental habits. Now it must shape a future in which the medium‐specific features of digital technologies become its core and in which print is absorbed into new hybrid modes of communication.

“The first wave of digital humanities work was quantitative, mobilizing the search and retrieval powers of the database, automating corpus linguistics, stacking hypercards into critical arrays. The second wave is qualitative, interpretive, experiential, emotive, generative in character. It harnesses digital toolkits in the service of the Humanities’ core methodological strengths: attention to complexity, medium specificity, historical context, analytical depth, critique and interpretation. Such a crudely drawn dichotomy does not exclude the emotional, even sublime potentiality of the quantitative any more than it excludes embeddings of quantitative analysis within qualitative frameworks. Rather it imagines new couplings and scalings that are facilitated both by new models of research practice and by the availability of new tools and technologies.”

As I eagerly read more, I realized that the tools of the first wave of digital humanities were trying to recreate what we built with Attenex Patterns. The second wave of digital humanities was partially implemented in Attenex Patterns and is extended through what I’ve been calling “content in context” as I research and design this tool set for applications like patent analytics and loyalty marketing. This new tool set provides the visual analytics needed for semantic networks, social networks, event networks, and geographical networks. Who would believe that I would find such great resources in a distant context – digital humanities – to extend my design to include features like curated story telling.

Once again I am reminded of the old proverb “When the student is ready the master will appear.” Like Russ Ackoff, I am grateful to a collection of students and colleagues who with gracious synchronicity point me to the human talent that I need when I need it.

Digital Humanities – Really? Yes, Really!

Pingback: Too Much to Know – The Death of the Long Form Book? | On the Way to Somewhere Else

Pingback: Beautiful Day at Duke University | On the Way to Somewhere Else

Pingback: Sifteo Siftables – So Near, So Far | On the Way to Somewhere Else

Pingback: Everything Old is New Again | On the Way to Somewhere Else

Pingback: Guest Post: Skip Walter Part II « UW Bothell Innovation Forum

Pingback: Know Thyself – UW Bothell Innovation Forum | On the Way to Somewhere Else

Pingback: Who’s Watching the Scientists? | On the Way to Somewhere Else

Pingback: Screwing Around with DH Workshop « triproftri

Pingback: Re-inventing University-Level Learning Workshop Resources | Innovation and Learning

Pingback: When Science and Art Dance – Business Results | On the Way to Somewhere Else

Thanks for sharing this fascinating exploration of the co-evolution of the humanities and technology.

It’s encouraging to read about some academics at the forefront pushing for paradigm-level shifts in the way we think about and promote learning. However, having returned to the academy a little over a year ago after a 15-year absence, I’m struck by how challenging it can be to make even small changes in curricula and programs. I’m not optimistic that many institutions will be willing and able to rise to the challenge, at least not in a timely fashion.

In a recent followup to his provocative essay last fall comparing Udacity and Napster, Clay Shirky offered further provocative – and, I believe, insightful – observations about why Your Massively Open Offline College Is Broken. While I suspect many academics will find his predictions threatening, I think, ultimately, they will have a positive impact on the broader provision of more effective learning opportunities, offline and online.

In response to one of the many more specific insights you shared, I was intrigued about the associations between software and [other?] art forms. I will look forward to following up on some of the links you provided, and meanwhile wanted to share one more, which I believe is also related to Kate’s emphasis on meaningfulness: Principle-centered Invention: Bret Victor on tools, skills, crafts and causes, a blog post in which I embedded a video, along with some notes (and a partial transcription), of Bret Victor’s inspiring demonstration and advocacy of empowerment in and through programming.

Reblogged this on Erik Champion.

Pingback: Breaking the Book – in book form | On the Way to Somewhere Else